By Leah Temper.

Are companies liable in their home countries for violations committed abroad? Are they liable anywhere? This has been the leading question in environmental justice law jurisprudence this year. The consensus so far has been mixed, with impunity generally ruling the day. But a recent Canadian court case gives cause for hope.

In January, Shell was tried in a court case in The Hague for the actions of its subsidiary Shell Nigeria. But the company was basically let off the hook with the court ruling that the parent company is not responsible for the actions of its “wayward child” and because the court accepted the company’s unsubstantiated claim that the spills were due to sabotage.

A few months later, a major blow was dealt to ATCA, the US Alien Tort Claims Act, when it was ruled in the Kiobel v. Shell case that the statute may no longer apply for abuses committed abroad. Since then another case has also been dismissed against Rio Tinto, on its evil behavior in Bougainville.

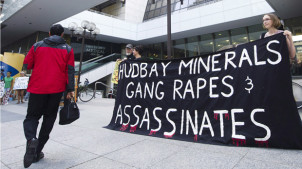

An Ontario court’s decision that the lawsuit brought against Hudbay Minerals regarding shootings, murder and gang-rape at its former nickel mine near Izabal Lake in Guatemala can proceed to trial in Canada may have important international implications. Superior Court of Ontario Justice Carole Brown has ruled that Canadian company Hudbay Minerals can potentially be held legally responsible in Canada for rapes and murder at a mining project formerly owned by Hudbay’s subsidiary in Guatemala. As a result of Justice Brown’s ruling, the claims of 13 Guatemalans will proceed to trial in Canadian courts. No similar lawsuit has made it past the preliminary stages and recent bills to regulate Canadian mining companies abroad, such as C-300, were tossed out.

According to the lawyer in the case for the 13 indigenous defendants, Murray Klippenstein: “As a result of this ruling, Canadian mining corporations can no longer hide behind their legal corporate structure to abdicate responsibility for human rights abuses that take place at foreign mines under their control at various locations throughout the world. There will now be a trial regarding the abuses that were committed in Guatemala, and this trial will be in a courtroom in Canada, a few blocks from Hudbay’s headquarters, exactly where it belongs. We would never tolerate these abuses in Canada, and Canadian companies should not be able to take advantage of broken-down or extremely weak legal systems in other countries to get away with them there.”

The Hudbay case sounds shocking and otherworldly when you hear it. HudBay is facing three lawsuits grouped together demanding tens of millions of dollars in damages after clashes between protesters and security forces at the Fenix nickel mine in 2007 and 2009. In one of the three cases, 11 women are alleging that the company was complicit in gang rapes perpetrated by the security personnel hired by the company during forced evictions to make way for the Fenix Nickel mine in El Estor, Guatemala, in 2007.

The other case involves the murder of a community leader who spoke out against the mine, Adolfo Ich Chaman, who was beaten by mine security guards, hacked with a machete and shot in the neck and killed. Another man was shot and is now in a wheelchair.

Yet sadly, such stories are commonplace, representing business as usual for many Canadian mining companies. The McGill Research Group Investigating Canadian Mining in Latin America has documented over 85 cases of socio-environmental conflicts involving Canadian companies in Latin America. Many of these entail human rights violations, but generally the “corporate veil” protects parent companies from being called to account in their home countries.

Lawyers for HudBay, have tried to have the case tossed out arguing that it would “wreak havoc” with this well-established corporate law principle that holds that parent companies are not liable for the actions of their subsidiaries. We can only say that for once, we hope they are right.