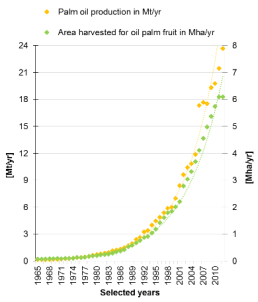

Palm oil is a booming business. While also used for cooking and in processed foods, over half of all palm oil produced now goes into soaps, cosmetics, biodiesel and other industrial purposes. Palm plantations are the fastest growing monoculture in the world and almost half of all global growth between the early 1960s and 2010 occurred in Indonesia – where they went from less than 0.07 million hectares in the early 1960s, to 6 million hectares in 2012. This huge expansion is linked to environmental burdens such as ecosystems and biodiversity impacts and on climate change through deforestation and drainage of peat lands. Plantation expansion has also infringed upon other types of land use and excludes groups of people from the land. The dispossession of people from their livelihood resource has often been violent and associated with social conflict.

The latest EJOLT report not only explains the history and causes of this booming business in Indonesia, it does the same for soy in Paraguay and large land investments in Ethiopia. And these case studies only serve to illustrate a broader analysis of patterns in the global biomass trade. Author Andreas Mayer from the Institute of Social Ecology at Alpen-Adria University commented that “The current expansion of agricultural lands in the global South puts massive pressure on local populations that are often threated with losing their livelihoods. This report aims to reveal the biophysical conditions and structural drivers of these conflicts and thus to identify conflict potentials that result from the dominant model of industrialized agricultural production”.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, global trade in agricultural products grew more than three times faster than agricultural production. Nearly all the new land that had been put into production since 1986 was used to produce export crops. While higher volumes of agricultural production and trade increased the global availability of agricultural products, their benefits and negative impacts are not evenly distributed globally. From a regional perspective, the surge in agricultural production for export is most pronounced in Latin America and in some Southeast Asian and Eastern European countries. This export orientation is often associated with negative impacts on food self-sufficiency and a potential threat to food sovereignty in the producing countries.

The report exa mines the global evolution of food production and international food trade and identifies related drivers of socio-environmental conflicts. Evidence from case studies of two important agricultural exporters – Indonesia and Paraguay – suggests that the focus on the extraction of primary materials for export (extractivism) in the agricultural sector can be linked to rising potential for socio-environmental conflict. This evidence in turn sheds new light on the third case study on Ethiopia, a country currently modernizing its agricultural sector with the aim of becoming a major exporter of agricultural products. Focusing on drivers of land use conflicts, the results presented in this report cover topics of importance for sustainability research and policy at large.

mines the global evolution of food production and international food trade and identifies related drivers of socio-environmental conflicts. Evidence from case studies of two important agricultural exporters – Indonesia and Paraguay – suggests that the focus on the extraction of primary materials for export (extractivism) in the agricultural sector can be linked to rising potential for socio-environmental conflict. This evidence in turn sheds new light on the third case study on Ethiopia, a country currently modernizing its agricultural sector with the aim of becoming a major exporter of agricultural products. Focusing on drivers of land use conflicts, the results presented in this report cover topics of importance for sustainability research and policy at large.

The authors conclude that the EU should revise the Common Agricultural Policy to strengthen small-scale farming, promote shorter production chains, support fair trade schemes, as well as to increase organic and permaculture practices. Henk Hobbelink from GRAIN said that “On this topic, the only real policy recommendation that I see is that the expansion of the commodity crops should be stopped and reversed, and land should be reverted to food production in the hand of small farmers.”