By Aaron Vansintjan.

Philippe* is the truck driver of a food bank in Montréal, Canada. Twice a week he drives to the headquarters of Moisson Montréal, the largest food bank in Canada. One day I go with him. We drive on the highway, past the endless strip malls, and arrive at a large warehouse. Once inside, we grab a cart and walk through the many aisles, accompanied by a man with a clipboard. We load the cart with crates of sparkling water, cookies, cans of carrots and peas, chips. We arrive at an enormous walk-in freezer filled with low-fat yoghurt, old vegetables, and mass-produced pastries. The man with the clipboard notes what we take and how much. Everything is standardized and measured.

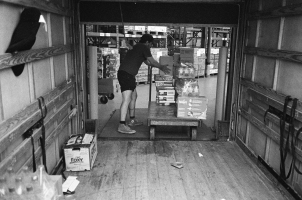

When we arrive back at the food bank, volunteers help us unload the truck. The empty boxes are sorted and stacked, later taken to the recycling center for some extra money—enough to cover gas expenses. The food is organized, put in the fridge or in storage. Some volunteers will cook, others prepare for the depannage d’urgence, when hundreds of Montréalers line up for a free basket of highly processed, expired, or damaged food. These people, many of whom are recent immigrants, single mothers, indigenous, or seniors, cannot pay for supermarket food and rely on the food bank for sustenance.

Who pays for all of this?

The food bank is not getting any money from the food industry to process their waste. They receive some support from the government for running specific programs like their collective kitchen or workshops. But as Thomas, the kitchen coordinator at the food bank remarked, “it’s not a free lunch. We have many costs, but the government won’t pay for them”.

These costs are translated into the unpaid labor of the volunteers. Eduardo, who has been at the food bank for three years, was previously an undocumented migrant and is now a permanent resident. Still, work is impossible to find. To be eligible for a monthly welfare cheque Eduardo has to spend up to twenty hours a week at the food bank as a form of community service. But this isn’t enough; it barely pays for rent. Lacking money, he relies on the food from the free baskets to survive. Like Eduardo, other volunteers at the food bank are mostly unemployable or retired citizens, spending long hours hauling and processing food waste.

This small organization in Montreal is part of a huge international network of food banks. The phenomenon of food banking is surprisingly recent; the first was started in 1967 in Phoenix, Arizona, and most food banks came into existence in the 1980s and 90s. In Canada alone, over 800,000 people use food banks every month. In the United States, over 46 million people use food banks every year. The European Federation of Food Banks distributes food to 5 million people every year. The Global FoodBanking Network has member food banks in 30 countries, and notes that food banks are opening more and more in the Global South.

Most food distributed by food banks comes from food retail, transport, and manufacturers. Most donations are like the stuff I saw in Moisson Montreal’s warehouse. In effect, the food industry’s unsaleable surplus is dumped onto poor populations that can’t pay for food at the supermarket. Uncountable volunteers all over the world are enlisted to process surplus. Some do it out of charity, others, people like Eduardo, do it because they cannot find work.

So who wins and who loses? When Feeding America, the primary US food bank network, surveyed food retailers on why they donated to food banks, the overwhelming response was not that it was ‘the good thing to do.’ They do it for the money. It is much cheaper to donate food waste and have it processed by countless volunteers than to pay for waste disposal costs. And so food banks can be seen as a classic case of ‘cost-shifting success’: without sufficient regulations, corporations got away with off-loading their waste onto the marginalized, forcing people like Eduardo and Philippe to spend unpaid hours sorting, cleaning, and eating trash.

How the food industry made waste ‘benevolent’

In the 1980s, the US government decided to cut welfare benefits and simultaneously set up a system of food commodity distribution. The state started funding small local food banks and providing them with massive amounts of surplus food commodities in state warehouses. Within two decades the largest food surplus recovery system was institutionalized with relatively small costs.

Yet despite the large role of the US government, the food industry’s part in the story cannot be overlooked. First of all, in the United States, the implementation of food bank-friendly policies can itself be seen as a form of rent-seeking beneficial primarily to the food industry. This was closely followed by a series of regulations called “Good Samaritan Laws” that ensured there were no legal risks for corporations to donate food waste, another example of how companies will guide policy in their favor.

Another illustration of the role of the food industry is the history of Canadian food banks. While food banks in Canada were started in the 1980s without any government aid, the network only really started growing when the food industry became more and more centralized in the 1990s. The centralization of the Canadian food system was largely due to two things: the Free Trade Agreement between Canada and the US and the North American Free Trade Agreement. As US corporations bought up and conglomerated the Canadian food industry, independent grocery stores were replaced by chain supermarkets. This meant more streamlined processing, transportation, and retail, which also meant an unprecedented need to dispose of food waste.

At the same time, globalization had led to the collapse of Canadian industry and the destruction of unions. All of a sudden many Canadians could not find jobs and also couldn’t receive welfare. Anti-poverty activists took matters into their own hands, petitioning supermarket managers to donate food waste, and started food banks in almost every community in Canada.

It was only in the 1990s that the Canadian food industry started to capitalize on this grassroots movement. When unions and local governments stopped providing resources to food banks, food retailers joined their boards, funded the construction of new warehouses to store donations, and ran advertising campaigns showing off how much food they had donated to the hungry. The food industry was able to brand their wasted products as a charitable act, done out of goodwill.

And so what started as a simple cost-shifting success became branded—by way of innovative corporate social responsibility campaigns—as benevolence.

Food banks as environmental injustice?

The high-input, high-output food industry makes a killing off of creating endless varieties of the same basic ingredients. Products with a “new flavor!” that no one buys, energy drinks that lost their fizz, labelling mistakes, all of these result in massive amounts of food waste.

But the futility of these random mistakes pales in comparison to the wider impacts of the food system based overproduction. Upstream impacts of the current industrial food regime include , soil erosion, pesticide use, biodiversity loss, and cruelty to animals. Downstream, as Julie Guthman has claimed, consumers of the food industry are victims of environmental injustice on a daily basis through the slow violence of toxic products. Food bank users are affected more than most. These wider costs of the food industry are distributed and unquantifiable.

Food banks as fuel for activism?

But there’s a kink in the story: food banks are much more than a canned handout. On one fall day, the food bank I studied was filled with migrant justice activists holding a barbecue celebrating their campaign to demand accessible food for undocumented migrants. A year before, the food bank had cooked for anti-austerity protests. They regularly organize community events and petition the local government for more accessible health care services.

As another worker at the food bank said, “it’s not only about food. It’s mostly not about food. It’s very political. We’re constantly playing the game, trying to push the neighborhood to change. If you don’t play the game, you’re not doing more than keeping people alive.” The director of the food bank emphasized that their activities were doiing much more than simply providing food to the hungry. “In simple terms, it’s making use of the fuel of the community resource.”

What the director meant was that the organization used any available resources—including food waste—to fuel their other activism. For example, they use it to ‘fund’ their collective kitchens and workshops that are intended to not only feed but to break through the isolation experienced by the neighborhood’s poor. Food organizes people, and through this they will often challenge the state or form coalitions with other organizations, scaling up their demands. Far from being helpless dupes, the food bank strategically uses food to attain social and political goals.

So here we have another picture that emerges: in a similar way to Raúl Zibechi’s description of ‘territories in resistance’—spaces that create economies separate from the state—food banks can use the resources available to enable new ways of doing activism. This is not environmental justice organizing. Instead, food banks create de-commodified forms of wealth to support marginalized communities and challenge other state policies.

Food banks in the context of the global environmental justice movement

As EJOLT has successfully documented, people around the world are engaging in creative forms of activism to challenge corporate cost-shifting and uneven ecological burdens. How do food banks fit within these movements, and can they be added to the atlas of environmental injustice struggles?

The case of food banks suggests that poor people’s responses to industrial waste aren’t always straightforward. While the food industry’s cost-shifting does have distributed and unequal impacts, those affected are choosing not to engage in an environmentalism of the poor against food waste . This could involve activism against over-processed and highly wasteful food, demands that corporations pay taxes on their food waste, or calls to decentralize the food industry . Instead, food bank users use food waste to fuel other kinds of activism—against state policies, against austerity, or against the social isolation that characterizes the lives of the poor in advanced capitalist economies.

We can’t pinpoint the environmental effects of the vast network that processes corporate food waste on a map. Nor is it possible to accurately quantify the benefits and costs that this same waste has for marginalized people in the Global North and South. The contradictions of food banks are not easily categorized in a database of environmental injustices. Yet for activists, researchers, and citizens, they can provide important lessons on the nature of corporate social responsibility, rent-seeking, and cost-shifting, and the ways people may transform waste from the industrial system to fuel for activism.

*Names have been changed.